Logistics Failing Russia in Ukraine, Could Limit US if China Attacks Taiwan

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has all but confirmed what many saw as evident following President Joe Biden‘s pullout from Afghanistan. As the 21st century unfolds, America’s international objective for the foreseeable future will be competing with adversarial great powers — including China and Russia.

Beyond its support for Ukraine, the United States has indirectly flexed its military muscle against Russia by carrying out drills in the Arctic. It has also teamed up with Israel to conduct naval exercises in an effort led by the U.S. 5th Fleet, which patrols the Gulf of Oman off the coast of Iran.

However, despite the nation’s military might, those who closely follow America’s naval operations say that the U.S. has failed to address a key critical point in military readiness— one which some say has become an “Achilles’ heel” that could leave the nation looking as battered and befuddled as Russia has looked to-date in its Ukraine War — if it were ever to lock horns with China.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), China builds 40% of the world’s merchant fleet and owns almost 12% of the world’s merchant ships. In contrast, the U.S. owns less than 3% of the world’s merchant ships and builds 0.1% percent of them.

“If we were in a conflict, would the lack of a merchant marine be a vulnerability? The answer is clearly yes,” Gregory Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), told Newsweek.

“Because we haven’t had to worry about the need for a merchant marine really since World War II, in any wartime scenario, we’ve forgotten how critical it would be in a wider conflict,” he added.

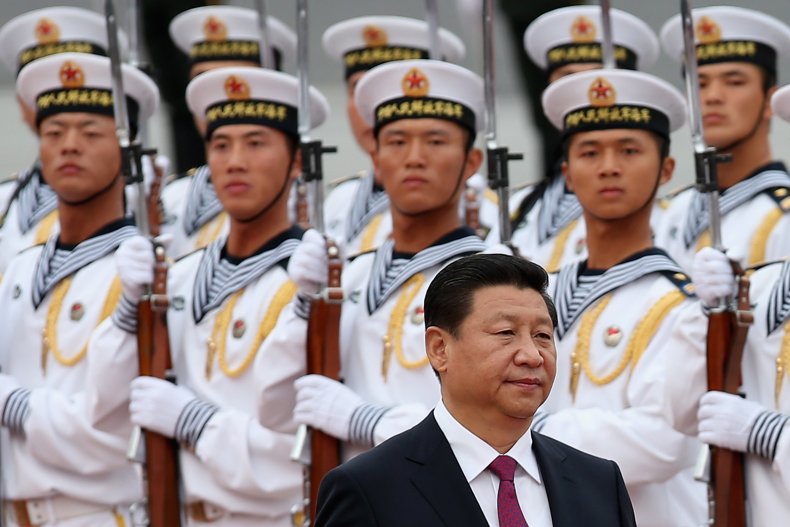

Photo by Feng Li/Getty Images

U.S. Merchant Marines are a fleet of civilian-manned ships that bear the U.S. flag. Their primary job consists of transporting cargo during times of peace and moving military supplies in times of war. It is an area of international commerce in which America falls well behind its adversaries.

Despite the current level of investment and notoriety it lacks compared to the Navy and Marine Corps, the U.S. Merchant Marine has historically played a critical role in international battles. During World War II, it “suffered a higher casualty rate than any branch of the military,” Smithsonian Magazine reports, as it hauled “vital” cargo to America and its allies.

“Our U.S. Merchant Marine is the backbone of our maritime capability,” Scott Ross, a spokesperson for the U.S. Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM) told Newsweek in a statement, “and the qualified mariners it employs is the lifeblood we rely on to power our strategic sealift portfolio. Sufficient and qualified mariners are essential to maintaining readiness.”

“The Maritime Administration (MARAD) assesses we have sufficient mariners to crew the entire organic surge fleet and commercial fleet simultaneously to meet wartime conditions,” he added, “but will be challenged if both fleets are required for prolonged operations.”

Not only would the U.S. struggle with its number of ships, but it also would likely not have the requisite personnel, according to a maritime union official.

“It really comes down to sustainment if there were a serious war,” Captain Don Marcus, president of the International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots labor union, told Newsweek. “There simply are not enough ships to sustain a long-term military operation, and not only the actual ships, but more importantly the mariners. Right now, there are not enough mariners for any long-term sealift crisis.”

The country’s current number of mariners could provide the U.S. military with ample support for a couple of months, he said, but when it would came time to relieve the crews, there would not be enough replacements.

In an April 2018 testimony before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, & Transportation’s Subcommittee on Surface Transportation, Maritime, Freight, and Ports, former Maritime Administrator Mark Buzby told lawmakers that the country was short by an estimated 1,800 mariners.

Lawmakers privy to maritime matters and the efforts of USTRANSCOM say that this force must not be forgotten as the U.S. focusses its agenda on preparing for foreign competition, especially if America one day finds itself reckoning with China over its claim to Taiwan.

With Taiwan sitting just about 100 miles off the coast of China, defending the island nation would put American troops close to enemy territory and far from home. Were the country to go up against its top competitor, such an effort could span months. Republican Congressman Rob Wittman of Virginia, who serves as the ranking member on the House Armed Services Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee, told Newsweek logistics coordination would be essential to victory.

“You go back to World War II, General Omar Bradley, I think said it best,” Wittman said. “He said, ‘Amateurs talk strategy. Professionals talk logistics.'”

Clerk of the United States House of Representatives

“I think (the U.S.) has to stand by its obligation to Taiwan,” he said. “If that is a sustained military operation, especially if it goes past 30 days, that is going to be incredibly, incredibly challenging for the United States.”

If China were to invade Taiwan, Wittman believes the U.S. “has to stand by its obligation” to the country, and speculates that doing so would require some sort of military operations. He says after a month of fighting the nation would face serious logistical challenges, as it would likely have to conduct maritime efforts in the Pacific.

Though logistics may not be what comes to top of mind when the public thinks of war, Wittman argues that those responsible for carrying out these efforts play as key of a role in battle as Marines, sailors, soldiers and airmen. Troops need fuel, munitions, food, and other supplies. When these lines are cut off, Wittman says a force cannot sustain itself.

Russia’s problems in Ukraine serves as a contemporary example. In early March, Vladimir Putin‘s invasion force was stalled during an attempted attack on Kyiv after they suffered mechanical breakdowns within its military convoy, resulting in lack of food and fuel for its troops. Ukraine’s Defense Ministry directly cites Russia’s overextension of its supply lines as a reason for its success in taking back conquered towns.

While Russia’s poor logistics can be attributed in part to its miscalculation that Putin’s forces could swiftly overpower the country in a matter of days, a Chinese invasion could look quite different.

Like Russia, Wittman says China has been testing what Taiwan’s response to an Chinese invasion might look like. Russian’s conducted “snap exercises” running tens of thousands of troops to the Ukrainian border prior to their invasion to gauge Ukraine’s response. Wittman notes that China has similarly sent aircraft towards the airspace of Taiwan to analyze their potential reactions.

With Beijing boasting the world’s largest navy, according to the U.S. Department of Defense, as well as a a sizable merchant marine, logistics could play out very differently for China in an invasion of Taiwan than they have for Russia in its invasion of Ukraine if the U.S. elected to respond.

Marcus said one of the reasons for the shortage of merchant marine ships is that after World War II, the maritime trade sector experienced one of the “first instance[s] of outsourcing and globalization.” It was during this time that U.S. shipowners adopted the practice of registering their vessels under “flags of convenience.”

Photo by Ramin Talaie/Corbis via Getty Images

Sailing under a “flag of convenience” allows a shipowner to avoid certain labor regulations and taxes imposed by their home countries. This is why countries like Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands stand as the world leaders in overall ship registration, according to the UNCTAD.

“Many commercial ships are registered under a flag that does not match the nationality of the vessel owner,” the UNCTAD writes. And while this may work just fine during times of peace, Poling said this system could prove to be a major liability during times of war.

According to a 2021 report by MARAD, America boasts just 180 privately-owned, oceangoing, U.S.-flagged ships, and just 96 of these carry “Jones Act” eligibility.

Under the Marchant Marine Act of 1920, often referred to as the “Jones Act,” ships with this designation are made capable “of serving as a naval and military auxiliary in time of war or national emergency.” This law does not mean all Jones Act ships will be adequate for military capabilities, yet the law mandates that those that are receive access to certain economic perks.

Under the act, shipping between U.S. ports can only be carried out by U.S.-flagged ships. Because these ships are more expensive to operate than those flying flags of convenience, the Congressional Research Service writes that this rule ensures “enough shipbuilding capacity and maintenance capability to support a domestic merchant fleet,” which in theory should provide for ample merchant marine assistance when the U.S. finds itself engaged in war.

“Although the U.S. flag commercial fleet has stabilized over the past couple of years, decades-long decline in its numbers have attritted critical mariner jobs that form the pool we rely on to bring our fleets to full operation,” Ross of USTRANSCOM told Newsweek.

“That is why we support MARAD’s efforts to leverage national maritime policies that advance the U.S. maritime interests in the global economy,” he added. “Increasing the demand for U.S. shipping will improve our maritime base, add critical mariner jobs, and reduce risk to our mission assurance.”

Poling also stressed the decline of America’s maritime industry as a contributor to the current situation, which could force the U.S. to rely on non-U.S.-flagged ships should it find itself engaged in war.

During an emergency situation, he stressed that these vessels may elect not to support logistics efforts in order to avoid both the risks of operating in war zones as well as pricy insurance premiums. Furthermore, having U.S.-flagged mariners also protect the nation from dealing with merchants who may not be willing to support the country’s wartime mission.

Clerk of the United States House of Representatives

Democratic Congressman John Garamendi of California, who serves as chair of the Readiness subcommittee within the House Armed Services Committee and as a member of the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee’s Subcommittee on Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation, knows how important that factor can be during an emergency situation.

Garamendi notes that during the first Gulf War the U.S. hired a ship and loaded it with military equipment to send to Iraq. The ship’s Pakistani sailors discovered what was being loaded and where the ship was headed and subsequently refused to carry the supplies, knowing their country was aligned with the U.S. and Kuwait in opposition against Iraq during this period.

“This is the Taiwan conundrum,” Garamendi told Newsweek. “If there was a conflict in the Pacific, we simply do not have the American vessels necessary to sustain the fight. We’d have to reach out to other countries and hire their ships to sustain the fight.”

“Then the question arises, would they be available?” he said. “China has the biggest fleet, would they make their ships available? No. South Korea, Japan, other places, we’d have to go out and hire vessels from around the world, and they would not be under American flag rules.”

Approximately 50% the world’s merchant fleet is owned by Asian companies, with U.S. allies Japan and South Korea presumably boasting 11% and 4% of the world’s total fleet, according to UNCTAD. Yet, if a world war were to break out near their ocean territory, it’s entirely possible those ships would have to be directed toward their own domestic efforts.

Garamendi said should a conflict arise, “we clearly do not have the logistical support.” However, he also stresses that such a conflict would not just be a potential military disaster, but it could prove to be an economic one as well.

Marcus agrees with that assessment. He told Newsweek that on its own the U.S. does not “have the ability to transport our own economic goods.” This means that America would be greatly impaired in its ability to respond to China through the type of economic sanctions it has placed on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

The World Economic Forum estimates that 90 percent of the world’s goods are transported by sea. A major disruption in the Pacific theater would likely raise the overall costs of doing business. If that disruption resulted in the U.S. and China ceasing joint business operations, Marcus said the nation would face a “consumer crisis.”

“Economic sanctions against China would have a huge impact on China, but it would also have a huge impact on the United States,” Marcus told Newsweek. “We’re very reliant, of course, on Chinese manufacturing, and we’re reliant on Chinese shipbuilding.”

Photo via Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images.

America’s interconnectedness with China would likely cause far more serious economic consequences in the U.S. if a similar level of sanctions were levied against China than what has been seen with the rise in gas prices in the wake of the Russia sanctions. And with a limited merchant marine, carrying out the logistics required for success could prove to be an uphill battle should the nation engage militarily over Taiwan.

Garamendi said that for the country to sustain itself in a Pacific conflict, it must look to bolster its fleet. Yet, aside from Navy programs, he stresses that within the country there are few shipbuilding operations left. And in order for a ship to be considered Jones Act- ready, it must be constructed in the United States.

Wittman sees a path forward, however, in a Philadelphia shipyard that he said has been able to cut costs and build ships quickly. He told Newsweek that this particular yard started their first variant of a commercial ship a year ago and have already begun building their second, surpassing expectations.

Garamendi said he has been developing what he calls the “National Maritime Security Program,” which would make the Jones Act fleet militarily useful. According to a Department of Transportation report, of the 180 U.S.-flagged ships, 157 are considered militarily useful. Garamendi said the others could be converted to meet this standard.

Under this plan, Garamendi said the Department of Defense would pay for alterations. This would allow merchant ships to be made ready for military logistics support in a shorter timeline than if the nation were to construct entirely new vessels.

“The U.S. maritime industry has simply atrophied and almost disappeared,” Garamendi told Newsweek. “There’s a phrase called ‘the tyranny of distance’ which is the Pacific. And therefore, the necessity of supplying, resupplying logistics becomes a critical factor in any action that the United States military could have to undertake in the Pacific.”

“The fact of the matter is that the United States does not have the logistical capability to support the military operations in the Pacific, period,” he added.