Switzerland Moves Ahead With Underground Autonomous Cargo Delivery

Gill Pratt, Toyota’s Chief Scientist and the CEO of TRI, believes that robots have a significant role to play in assisting older people by solving physical problems as well as providing mental and emotional support. With a background in robotics research and five years as a program manager at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, during which time he oversaw the DARPA Robotics Challenge in 2015, Pratt understands how difficult it can be to bring robots into the real world in a useful, responsible, and respectful way. In an interview earlier this year in Washington, D.C., with IEEE Spectrum’s Evan Ackerman, he said that the best approach to this problem is a human-centric one: “It’s not about the robot, it’s about people.”

What are the important problems that we can usefully and reliably solve with home robots in the relatively near term?

Gill Pratt: We are looking at the aging society as the No. 1 market driver of interest to us. Over the last few years, we’ve come to the realization that an aging society creates two problems. One is within the home for an older person who needs help, and the other is for the rest of society—for younger people who need to be more productive to support a greater number of older people. The dependency ratio is the fraction of the population that works relative to the fraction that does not. As an example, in Japan, in not too many years, it’s going to get pretty close to 1:1. And we haven’t seen that, ever.

Solving physical problems is the easier part of assisting an aging society. The bigger issue is actually loneliness. This doesn’t sound like a robotics thing, but it could be. Related to loneliness, the key issue is having purpose, and feeling that your life is still worthwhile.

What we want to do is build a time machine. Of course we can’t do that, that’s science fiction, but we want to be able to have a person say, “I wish I could be 10 years younger” and then have a robot effectively help them as much as possible to live that kind of life.

There are many different robotic approaches that could be useful to address the problems you’re describing. Where do you begin?

Pratt: Let me start with an example, and this is one we talk about all of the time because it helps us think: Imagine that we built a robot to help with cooking. Older people often have difficulty with cooking, right?

Well, one robotic idea is to just cook meals for the person. This idea can be tempting, because what could be better than a machine that does all the cooking? Most roboticists are young, and most roboticists have all these interesting, exciting, technical things to focus on. And they think, “Wouldn’t it be great if some machine made my meals for me and brought me food so I could get back to work?”

But for an older person, what they would truly find meaningful is still being able to cook, and still being able to have the sincere feeling of “I can still do this myself.” It’s the time-machine idea—helping them to feel that they can still do what they used to be able to do and still cook for their family and contribute to their well-being. So we’re trying to figure out right now how to build machines that have that effect—that help you to cook but don’t cook for you, because those are two different things.

How can we manage this temptation to focus on solving technical problems rather than more impactful ones?

Pratt: What we have learned is that you start with the human being, the user, and you say, “What do they need?” And even though all of us love gadgets and robots and motors and amplifiers and hands and arms and legs and stuff, just put that on the shelf for a moment and say: “Okay. I want to imagine that I’m a grandparent. I’m retired. It’s not quite as easy to get around as when I was younger. And mostly I’m alone.” How do we help that person have a truly better quality of life? And out of that will occasionally come places where robotic technology can help tremendously.

A second point of advice is to try not to look for your keys where the light is. There’s an old adage about a person who drops their keys on the street at night, and so they go look for them under a streetlight, rather than the place they dropped them. We have an unfortunate tendency in the robotics field—and I’ve done it too—to say, “Oh, I know some mathematics that I can use to solve this problem over here.” That’s where the light is. But unfortunately, the problem that actually needs to get solved is over there, in the dark. It’s important to resist the temptation to use robotics as a vehicle for only solving problems that are tractable.

It sounds like social robots could potentially address some of these needs. What do you think is the right role for social robots for elder care?

Pratt: For people who have advanced dementia, things can be really, really tough. There are a variety of robotic-like things or doll-like things that can help a person with dementia feel much more at ease and genuinely improve the quality of their life. They sometimes feel creepy to people who don’t have that disability, but I believe that they’re actually quite good, and that they can serve that role well.

There’s another huge part of the market, if you want to think about it in business terms, where many people’s lives can be tremendously improved even when they’re simply retired. Perhaps their spouse has died, they don’t have much to do, and they’re lonely and depressed. Typically, many of them are not technologically adept the way that their kids or their grandkids are. And the truth is their kids and their grandkids are busy. And so what can we really do to help?

Here there’s a very interesting dilemma, which is that we want to build a social-assistive technology, but we don’t want to pretend that the robot is a person. We’ve found that people will anthropomorphize a social machine, which shouldn’t be a surprise, but it’s very important to not cross a line where we are actively trying to promote the idea that this machine is actually real—that it’s a human being, or like a human being.

So there are a whole lot of things that we can do. The field is just beginning, and much of the improvement to people’s lives can happen within the next 5 to 10 years. In the social robotics space, we can use robots to help connect lonely people with their kids, their grandkids, and their friends. We think this is a huge, untapped potential.

Where do you draw the line with the amount of connection that you try to make between a human and a machine?

Pratt: We don’t want to trick anybody. We should be very ethically stringent, I think, to not try to fool anyone. People will fool themselves plenty—we don’t have to do it for them.

To whatever extent that we can say, “This is your mechanized personal assistant,” that’s okay. It’s a machine, and it’s here to help you in a personalized way. It will learn what you like. It will learn what you don’t like. It will help you by reminding you to exercise, to call your kids, to call your friends, to get in touch with the doctor, all of those things that it’s easy for people to miss on their own. With these sorts of socially assistive technologies, that’s the way to think of it. It’s not taking the place of other people. It’s helping you to be more connected with other people, and to live a healthier life because of that.

How much do you think humans should be in the loop with consumer robotic systems? Where might it be most useful?

Pratt: We should be reluctant to do person-behind-the-curtain stuff, although from a business point of view, we absolutely are going to need that. For example, say there’s a human in an automated vehicle that comes to a double-parked car, and the automated vehicle doesn’t want to go around by crossing the double yellow line. Of course the vehicle should phone home and say, “I need an exception to cross the double yellow line.” A human being, for all kinds of reasons, should be the one to decide whether it’s okay to do the human part of driving, which is to make an exception and not follow the rules in this particular case.

However, having the human actually drive the car from a distance assumes that the communication link between the two of them is so reliable it’s as if the person is in the driver’s seat. Or, it assumes that the competence of the car to avoid a crash is so good that even if that communications link went down, the car would never crash. And those are both very, very hard things to do. So human beings that are remote, that perform a supervisory function, that’s fine. But I think that we have to be careful not to fool the public by making them think that nobody is in that front seat of the car, when there’s still a human driving—we’ve just moved that person to a place you can’t see.

In the robotics field, many people have spoken about this idea that we’ll have a machine to clean our house operated by a person in some part of the world where it would be good to create jobs. I think pragmatically it’s actually difficult to do this. And I would hope that the kinds of jobs we create are better than sitting at a desk and guiding a cleaning machine in someone’s house halfway around the world. It’s certainly not as physically taxing as having to be there and do the work, but I would hope that the cleaning robot would be good enough to clean the house by itself almost all the time and just occasionally when it’s stuck say, “Oh, I’m stuck, and I’m not sure what to do.” And then the human can help. The reason we want this technology is to improve quality of life, including for the people who are the supervisors of the machine. I don’t want to just shift work from one place to the other.

Can you give an example of a specific technology that TRI is working on that could benefit the elderly?

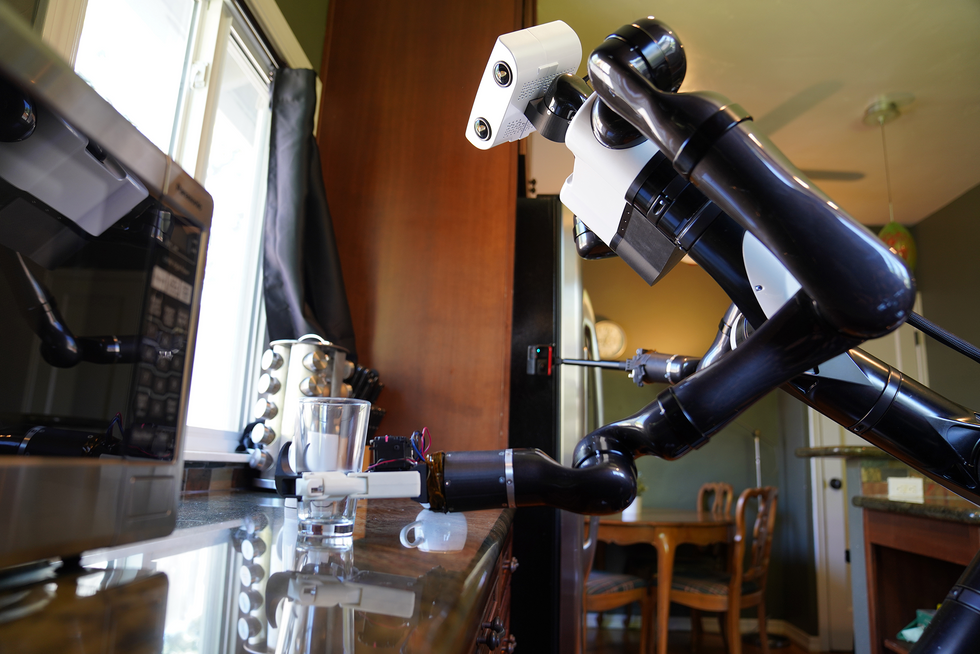

Pratt: There are many examples. Let me pick one that is very tangible: the Punyo project.

In order to truly help elderly people live as if they are younger, robots not only need to be safe, they also need to be strong and gentle, able to sense and react to both expected and unexpected contacts and disturbances the way a human would. And of course, if robots are to make a difference in quality of life for many people, they must also be affordable.

Compliant actuation, where the robot senses physical contact and reacts with flexibility, can get us part way there. To get the rest of the way, we have developed instrumented, functional, low-cost compliant surfaces that are soft to the touch. We started with bubble grippers that have high-resolution tactile sensing for hands, and we are now adding compliant surfaces to all other parts of the robot’s body to replace rigid metal or plastic. Our hope is to enable robot hardware to have the strength, gentleness, and physical awareness of the most able human assistant, and to be affordable by large numbers of elderly or disabled people.

What do you think the next DARPA challenge for robotics should be?

Pratt: Wow. I don’t know! But I can tell you what ours is [at TRI]. We have a challenge that we give ourselves right now in the grocery store. This doesn’t mean we want to build a machine that does grocery shopping, but we think that trying to handle all of the difficult things that go on when you’re in the grocery store—picking things up even though there’s something right next to it, figuring out what the thing is even if the label that’s on it is half torn, putting it in the basket—this is a challenge task that will develop the same kind of capabilities we need for many other things within the home. We were looking for a task that didn’t require us to ask for 1,000 people to let us into their homes, and it turns out that the grocery store is a pretty good one. We have a hard time helping people to understand that it’s not about the store, it’s actually about the capabilities that let you work in the store, and that we believe will translate to a whole bunch of other things. So that’s the sort of stuff that we’re doing work on.

As you’ve gone through your career from academia to DARPA and now TRI, how has your perspective on robotics changed?

Pratt: I think I’ve learned that lesson that I was telling you about before—I understand much more now that it’s not about the robot, it’s about people. And ultimately, taking this user-centered design point of view is easy to talk about, but it’s really hard to do.

As technologists, the reason we went into this field is that we love technology. I can sit and design things on a piece of paper and feel great about it, and yet I’m never thinking about who it is actually going to be for, and what am I trying to solve. So that’s a form of looking for your keys where the light is.

The hard thing to do is to search where it’s dark, and where it doesn’t feel so good, and where you actually say, “Let me first of all talk to a lot of people who are going to be the users of this product and understand what their needs are. Let me not fall into the trap of asking them what they want and trying to build that because that’s not the right answer.” So what I’ve learned most of all is the need to put myself in the user’s shoes, and to really think about it from that point of view.